ARTICLE

Hazrat Inayat Khan: From Maestro to Master

Part one of an essay on this remarkable

musical pioneer, by the UK's leading critic, broadcaster and author, Jameela

Siddiqi.

published in the

January 2004 issue of veena Indian Arts Review.

The year is 1910, and a ship sails

into New York harbour. One of the passengers, an Indian musician, catches

his first glimpse of the Statue of Liberty. On sighting that gigantic and

impressive monument, he observes that it is 'awaiting the moment to rise

from material liberty to spiritual liberty.' Little could anyone have guessed

that towards the end of his brutally short life-span of forty-five years

(1882-1927), he was destined to play a pioneering role in laying the foundations

for bridges between the spiritual and material worlds, at that time clearly

defined as 'East' and 'West.' In his biography, that journey is described

as being transported 'by destiny from the world of music and poetry to

the world of industry and commerce.'

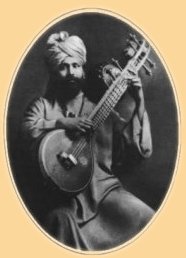

The Sufi teacher Hazrat Inayat Khan

(of Baroda) was a significant pioneer in two ways. He was the first person

to bring Indian music to the West and he was also the first to transport

Sufism to the West. Ironically, he had to give up the former - his first

love -- in order to pursue the latter, driven by an overwhelming and compelling

urge going against all the odds, to spread the spiritual message of Sufism

in the western world. In his own words: 'I gave up my music because I had

received from it all I had to receive. To serve God one must sacrifice

the dearest thing, and I sacrificed my music, the dearest thing to me.'

He arrived in the West at a time

when Europe stood on the threshold of the First World War, the after effects

of which were to leave western society permanently and irrevocably changed.

European wars and politics were to touch his personal and professional

life in many different ways. Inayat Khan was able to observe the impact

of nationalism and jingoism at first hand and while the First World War

offered a backdrop against which he was able to perfect his groundbreaking

theories on the mysticism of sound and music in terms of discord and harmony

as represented by warlike nationalism, while his daughter, Noorunissa,

many years after his death, found herself in the midst of the Second World

War as a heroine of the French Resistance movement, and was eventually

shot by the Nazis.

In today's India, unless you specify

you mean 'Sufi' Inayat Khan, it is generally assumed that you are referring

to one of the two other eminent classical musicians of the same name. The

vast repository of textbooks on Indian classical music make absolutely

no reference to Hazrat Inayat Khan who was, undoubtedly, not only one of

the greatest musicians of his time, but had also composed poems in Farsi,

Urdu and Hindi. These recordings, made on 78 r.p.m records lay neglected

in mint condition within the EMI archives in London for some 90 years!

Some amazing detective work, carried out by the Australian scholar Michael

Kinnear in 1994, uncovered the entire collection of 31 songs recorded by

Inayat Khan during his stay in Calcutta in 1909. On hearing these recordings

and Inayat Khan's full-throated ghazals, khayals, taranas, bhajan and dhrupad,

one cannot help but realise that this is the real thing.

In India itself, Inayat Khan's name

in connection with classical music seems to have lapsed from local memory

once he left for America in 1910. While that is understandable, what is

really surprising is that Inayat Khan's most important publication on music,

Minqar-e-Musiqar (Allahabad Indian Press, 1913), one of the most

definitive works on the theory and practice of Indian classical music (including

full delineations of some 450 raags!), has never ever been translated into

English or any other language, given the vast demand overseas for authoritative

works on Indian music.

|