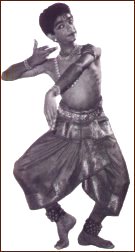

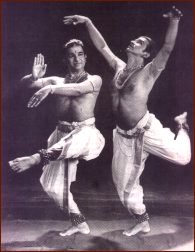

The Concept of the Male Dancer

From "A Dancer on Dance" written by V.P. Dhananjayan, published by Bharata Kalanjali

Indian dance is very popular today.

In popular parlance, it is the in-thing. There are different classical

Indian Dances, the most famous of which are Bharatanatyam, Kathakali, Odissi,

Kathak, Manipuri and Kuchipudi. These dances arouse public enthusiasm

and consequently such performances now draw knowledgeable and highly sophisticated

audiences, compared to those of past decades.

Amidst all this renaissance of interest

in Dance somehow a wrong notion has crept into the minds of our people

that dancing is meant only for women. The historical and socio-cultural

factors that led to this misconception are many. It is a fact

that for many decades, dance has been a near monopoly of women, be it in

the South or the North. Nowadays the male dancer is a rare phenomenon

and it happens that a section of the public looks down upon him.

Men may become dance teachers, they may provide nattuvangam and musical

accompaniment and do everything else needed to make it possible for women

to dance, but if they themselves don ankle bells and start to dance, they

are put down as effeminate upstarts in an exclusively female domain.

The traditional, meaning hereditary,

dance teachers, usually refuse to teach men; and the less said about women

teachers in this regard the better. This is very surprising since

the very concept of Dance is masculine in origin. Nataraja, meaning the

king of performers, the patron deity of dancers is male and according to

Indian scripture, the originator of Dance.

Parallels from nature also, can

be drawn showing that the male is more oriented towards the movements that

appear dance-like to us. The dance of the peacock, the gait of the

male swan or the stance of a lion.

The writer of Natya

Sastra and all its great commentators have been men. So have been

the foremost masters and composers of this medium of dance.

In folk and tribal dancing, the performers

are generally men while women are mostly excluded from magical and ritual

dancing. Thus the present social prejudice against the male dancer is entirely

without basis. It is interesting to note that the Natya Sastra, the

ancient Indian science of dramaturgy views dance as a male prerogative.

The stylistic elements of its techniques are described under 'Tandavalakshana',

the male overtones of which term are obvious. 'Lalitha Nrithyam',

the soft and gentle type of dance is only a part of 'Kaisiki Vritti' one

of the four dramatic presentations described in texts (the others Arabhati,

Satvathi and Bharathi).

It is believed that Parvathi, the consort

of Nataraja Siva, introduced the 'Lasya' or the delicate-feminine mode

into Dance. Yet as compared with her consort Nataraja, her dance

finds an insignificant place in literature, over-shadowed, as it were,

by the extreme and all-pervasive vigour of Nataraja's 'Tandava'.

Apart from this divine couple there are quite a few personages from our

mythology who are associated with the art of dancing in one way or the

other and among these, invariably men outnumber women. Krishna, the

frolic-some stealer of hearts is a dancer. Arjuna was conscripted

by Indra to judge the better amongst the celestial dancers, Rambha and

Urvasi. And while in exile, Arjuna taught dance as Brihannala to

Uttara. Kamadeva, Ganesha, Anjaneya and even Ravana were all supposed

to be masters of music and dance. Bharata and his hundred illustrious

sons who propagated this art form throughout our country can also be cited

as evidence from the Itihasas.

According to the more substantial

evidence from literature, men have been predominantly associated with dance

from ancient times. Bharata, the author of Natyasastra, Nandikeswara

the author of Abhinayadarpana, Dhananjaya who wrote Dasarupaka, and many

other writers and commentators, including Dattila and Kohala alluded to

by Nandikeswara in the introduction of his oft referred treatise, were

men.

So was Jaya Senapathi,

of Nrittaratnavali and Ilango Adigal, the author of Silappadikaram (Tamil

literary work) which devotes a chapter exclusively to an erudite discussion

of music and dance as it existed then.

The heritage of Indian Dance embraces

several forms which can be broadly classified as classical, folk and tribal.

Apart from the major classical styles, there are at least a dozen other

forms so highly developed that they deserve to be ranked along with the

principal styles mentioned earlier. An interesting feature of these

diverse styles is that, most of them were originally intended for men alone.

It is only recently that women have been taking part in them.

Looking back again to scriptures, Dance

originally existed as dance dramas. Kathakali, Bhagavathamela, Kuchipudi,

Krishnattam, etc., were all presentations of drama through the medium of

dance. With this vast back-ground supporting the existence and virtually

the pre-eminence of the male dancer, it is highly regrettable that so many

misconceptions continue today. There are some people who hold that

dancing should be delicate and graceful, even if a man is the performer.

Some teachers go to the extent of coercing their male students to imitate

their female counterparts in the departments of dress, ornamentation and

presentation.

The cumulative effect of these misconceptions

of the public and the mis-direction of the teachers is such that very few

men are taking to dance, fewer still making the grade to become professionals.

This apart, there is immense social and parental pressure on boys to become

doctors and engineers so that a lucrative career is assured. With

all this psychological stigma, social approbation and economic sanctions,

it is not surprising that dance is fast becoming more oriented towards

the fair sex. On the other hand, this is something akin to damning

with faint praise, if a boy is delicately featured and minces to match,

he is considered a fit candidate for dance lessons.

Unless these trends are reversed

by educating public opinion, the dignity and prestige of this magnificent

art form will be lessened, probably for ever, by excluding the male element

from it. Let us hope it will not come to pass.